Before I count down I want to mention those groups which narrowly missed out on making the list. The fauna of the Zechstein sea, particularly fossils found in South Yorkshire, interest me a lot as they are my local fossils. I have blogged about them a few times and hope to do something more academic with them too. I also briefly considered adding crocodiles to the list, as their past threw up many interesting variations which look nothing like our modern crocs, but I know little about them (I would say that if you want to be a vertebrate palaeontologist then crocodiles may be a great area to study). I also considered adding jawless, armoured fish from the Silurian, as I had a lecture on them today and found them very interesting, but they just missed out to some groups which I have liked for longer. So, onto the list...

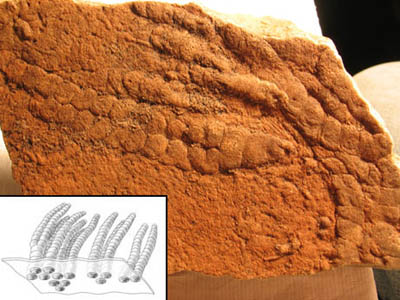

10: Crinoids

|

| A crinoid fossil from Doncaster Museum. |

9: The Dinosaur to Bird Transition

It is well established now that birds evolved from dinosaurs, which is testament to the hard work of many palaeontologists. Laboriously comparing traits on fragmented fossils, they had to rely completely on a few rare transitional fossils to come to their conclusions. No genetic testing was available, only comparison of fossils. If we had no Archaeopteryx then our understanding might have been rather different. We are fortunate now to have quite a range of fossils spanning this transition, with feathered dinosaurs on one side, primitive birds on the other, and a spectrum in between, where individual traits can be seen to gradually change. It also allows me to include a group I like but have not included in this list - dromaeosaurs. Those swift, vicious hunters were closely related to the ancestor of birds, possessing many key skeletal precursors and covered in many feathers. This group of fossils speaks of my childhood love of dinosaurs (which still exists in a non-academic sense, enough to get a tattoo of one) and of my love of evolution. I do not intend to study them academically, though I would not turn down a good look at Archaeopteryx and will undoubtedly write about them in future.

8: Thyreophora

These are the armoured dinosaurs. This group includes the stegosaurs of the Jurassic and the ankylosaurs of the Cretaceous, along with the nodosaurs which tend to get less attention (though thyreophorans as a whole tend to get overlooked, except perhaps Stegosaurus itself). The stegosaurs were a favourite of mine as a child, with Tuojiangosaurus being an obscure preference. These have leapt into my list because I attended a lecture about the thyreophora just last week, by a friend of mine, and was reminded how fascinating they can be. I also have an ankylosaur-obsessed friend, so I hear about them a lot. They might have been slow and stupid, but it worked! They were incredible beasts and deserve more attention. I think if I were fortunate enough to have the skeleton of just one dinosaur on display, it would have to be some sort of stegosaur.

7: Fossils of the Hunsrück-Schiefer

|

| A beautiful pyrite-preserved brittle star Ophinurina lymani. |

6: The Fish to Amphibian Transition

Another fascinating evolutionary transition which is documented well by the fossils, yet manages to keep astonishing us. The "fishibian" Tiktaalik is becoming one of the main transitional forms mentioned, though it would need a lot more publicity to surpass Archaeopteryx in fame. One of the reasons this group of fossils makes my list is because Neil Shubin's book Your Inner Fish had a big impact on me, informing my understanding of evolution and helping reignite my passion for palaeontology. A good portion of the book is dedicated to Tiktaalik, which the author was instrumental in finding.

5: Eurypterids

These are the mighty sea scorpions, scourges of the Silurian seas. Some of them grew enormous, up to around eight feet long, yet recent studies sadly suggest that they were not the vicious sea monsters we would love them to be. They most likely spent a lot of time lurking, waiting for prey to come into close proximity, before they attacked. They did not have incredible strength, so likely went for weak and small prey in the sea. Even so, they are still impressive and their fossil remains are often beautiful and not too difficult to recognise. I managed to get a good look at quite a few eurypterid fossils last summer at the museum, Pterygotus and Slimonia, which gave me an interest in them. I enjoyed having to closely inspect them and try to work out how many segments each had, while attempting to learn the names of each part. I would love to see the giant sea scorpion up close some day. And for the record, they are not ancestors of terrestrial scorpions.

4: The Transition from Reptiles to Mammals

This is arguably the most beautiful transition in the fossil record. We are exceptionally lucky to have numerous well-preserved fossils documenting this pivotal change in our history. It is most famous for the fact that we can see the changes from the reptilian jaw, which contains around seven bones, to the mammalian condition where there is one main jaw bone. What is incredible about this is that the fossils show the other jaw bones becoming reduced and migrating to the ear, where they have become the inner ear bones of all mammals. There are even some fossils with double hinges on their jaws, caught in the act in a way. The changes in the jaw and ear are alongside changes from reptilian motion (side to side) to the up-down undulation of mammalian movement; changes in dentition and the development of a secondary palate, allowing them to chew; the development of fur and warm blood, and a whole host of other changes which are intimately linked (usually metabolism and consumption) and documented by the fossils. Astonishing!

3: The Cambrian "Explosion" Fauna

The fossils of the Cambrian are undoubtedly some of the most important, as we find the earliest examples of most of the modern phyla during a time of exceptional evolutionary creativity. Not only are there the familiar groups, such as trilobites and even members of our own phylum, but there are a host of oddballs which defy classification, such as Opabinia. My favourites during this period are the unusual arthropods, such as Anomalocaris, and lobopod worms such as Hallucigenia (pictured). There are a few famous sites of exceptional preservation during the Cambrian diversification event, giving us amazing windows to peer into the ancient world. Stephen Jay Gould made the Cambrian fossils of the Burgess Shale the stars of the show in his book Wonderful Life which I thoroughly recommend. This is likely a very predictable group for my list, as our understanding of Ediacara impacts on our interpretations of what was going on during the Cambrian. There are always new ideas popping up trying to explain the Cambrian explosion and it has been a constant source of fascination for palaeontologists for a while now.

2: Trilobites

I would be very surprised if trilobites did not make the list of the vast majority of palaeontologists, if they were asked to make such lists. Anyone interested in palaeontology should read Richard Fortey's Trilobite and marvel at the myriad forms and uses of this important fossil group. Trilobites are iconic, fascinating and are often beautifully preserved fossils. They exploited pretty much every marine niche possible and had stunning diversity, before their demise at the end of the Permian. They are justifiably one of the most studied groups, better known than some extant groups! They are not just wonders to gaze at, but are also heavily used in biostratigraphy, biogeography, palaeoecology and more. I have done a few blogs on trilobites, so this should have come as no surprise. I have sadly not been anywhere to find any yet, but that will be remedied soon. I'd love to work on them too.

1: Small Shelly Fauna

Often referred to as SSFs these may seem like an odd group to have at number one. The informed or observant reader might have predicted this though. The blog icon is Microdictyon, a lobopod worm and SSF which is related to the aforementioned Hallucigenia. SSFs are microscopic mineralised parts which are largely enigmatic, though some are recognisable. They are found during the earliest stages of the Cambrian, right before the Cambrian explosion and right after the Ediacaran fossils. They herald the arrival of mineralised parts (not quite true, as there are a couple of genera at the end of the Ediacaran with hard parts) but we do not know what many of them are. Some fortunate soft tissue preservation has shown some of them to be parts of bigger organisms; the tiny, net-like sclerites of Microdictyon for example. There are cap-like shells which are micromolluscs, but many of them remain incredibly mysterious, though they are useful in biostratigraphy and overlap with trilobite zones which occur a bit later. I liked this group before I started getting really into Ediacarans, though I don't know too much about them. They are currently my favourite topic of research as I am considering doing a major project on them, which I am really looking forward to.

So there you go, my top ten. While I was writing it I felt like swapping around the order, but this list is meant to be transient, so I thought I would stick to it how I originally order it rather than constantly shuffling them around. I can possibly guess what you are currently thinking and I bet the words "nerd" or "geek" pop up at least once.